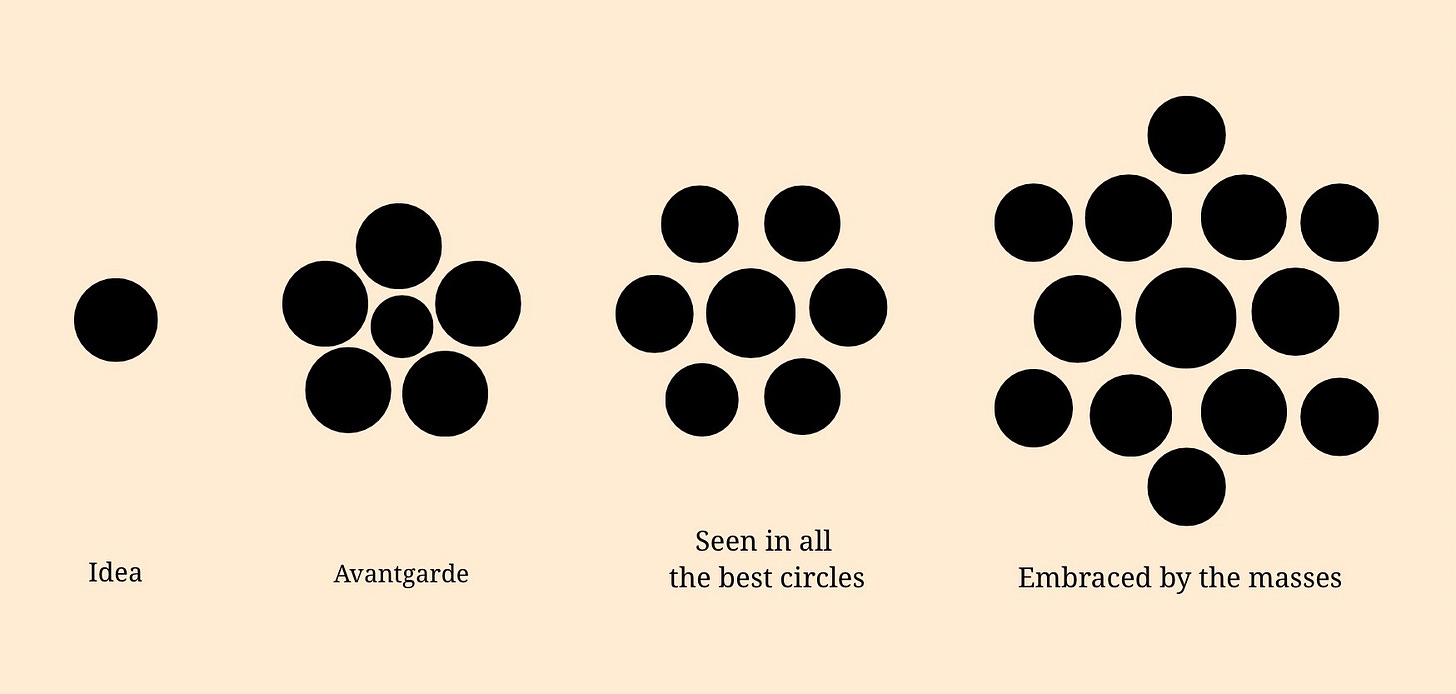

There’s a rhythm to trends — not just in their silhouettes or colors, but in how they emerge, settle, and dissolve. It’s said that a trend takes around four years to rise, two years to fully circulate, and another four to fade back into obscurity, only to be revived once enough time has passed to make it feel new. For something supposedly momentary, fashion moves in surprisingly repetitive cycles.

Infinite Options, Identical Outcomes

And yet, the way we experience trends today feels far from linear. We live in a cultural moment where aesthetics multiply in real time — microtrends swarm our feeds, overlap, contradict one another, or reappear under slightly altered names. Ballet flats and Balenciaga boots trending on the same timeline. Y2K and Old Money and Vanilla Girl and Mob Wife and That Girl and whatever this week’s name is for minimalism. A multiverse of aesthetics, constantly refreshed.

One could argue we have more choice than ever. But with this flood of options, something curious has happened: we haven’t become more diverse, more creative, or more self-defined. We’ve become visually interchangeable.

Everyone is different in exactly the same way.

It’s not hard to understand why. Trends, like all heuristics, are mental shortcuts — simple, efficient ways to navigate a complex world. They help us decide what to wear, how to present ourselves, and how to feel like we’re keeping up. In that sense, trends are a form of safety: socially approved, recognizably coded, comfortably familiar. But safety, as it turns out, is not the same as clarity. And imitation is not the same as identity.

The Cult of Aesthetics and The Comfort of Not Belonging

A YouTuber (Sorelle Amore) refered to this as the “cult of aesthetics,” describing how people — especially online — have started to flatten their personalities into digestible visuals and call it empowerment. I found that deeply resonant, not just because I’ve seen it play out professionally and culturally, but because I’ve done it myself, more times than I can count. I’ve hidden inside someone else’s aesthetic, followed trends because I was cognitively primed to do so, dressed in ways that said all the right things — just not anything I personally believed.

What constantly brings me back to myself is that the idea of belonging, of visually aligning with a tribe, has never been something I found comfortable. Even when I tried it, the feeling of being part of a group — aesthetic or otherwise — felt like a subtle erosion of self. I’ve never wanted to represent a category, not even the category of “individual.” While I don’t dress in extreme or radically unconventional ways all the time, the only identity I’ve ever felt aligned with is my own. And even that evolves.

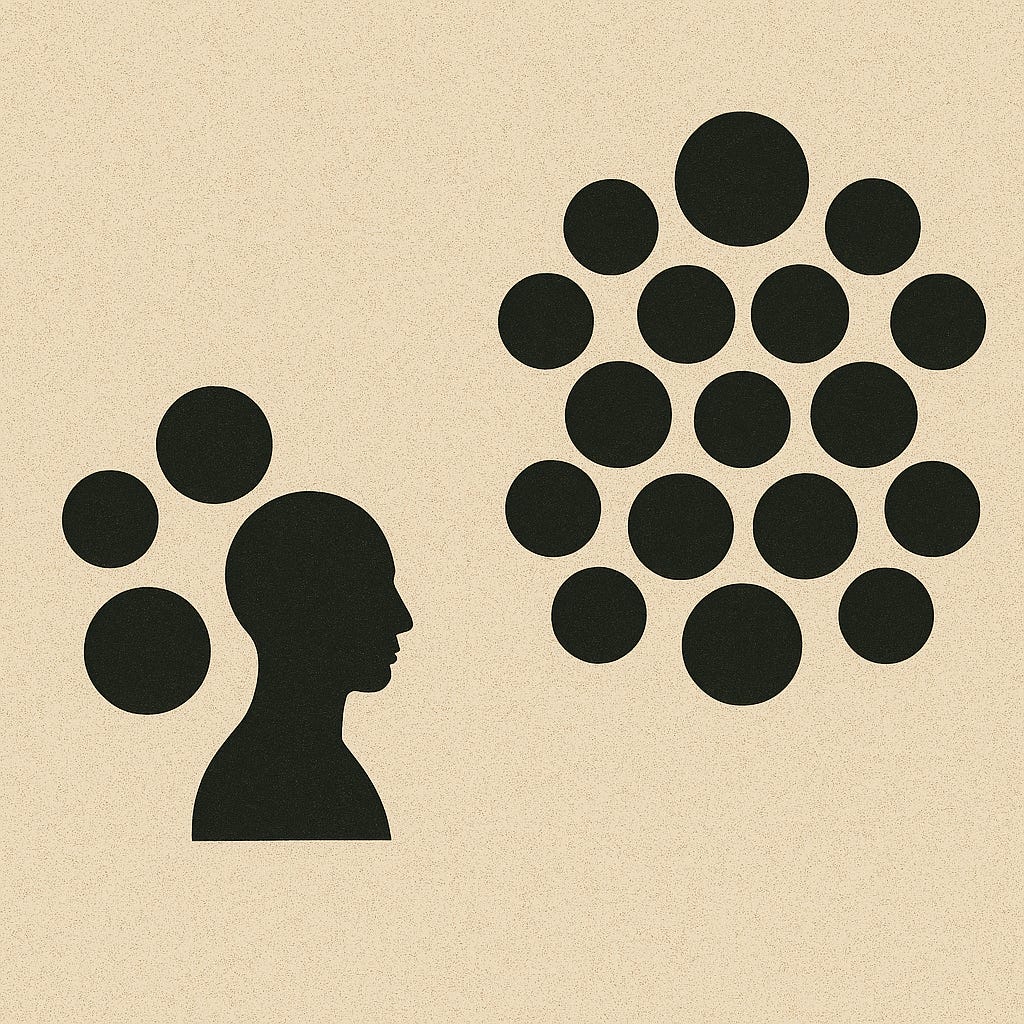

A Third Option: The Why Behind the What

This, I think, is where the binary breaks down. We’re often told that you can either follow trends or resist them — conform or rebel, signal belonging or signal independence. But I don’t think those are the only options. There’s a third approach, one that has less to do with the external outcome and more to do with the internal motivator.

Not what you wear, but why you wear it.

Because someone dressing entirely on-trend out of genuine joy or curiosity may be far more self-aligned than someone avoiding trends out of fear of being seen as basic. Resistance, too, can be performative. The key difference, I believe, is intentionality. When your choices are rooted in self-knowledge, your wardrobe becomes a tool for expression, experimentation, even transformation — not just a costume for belonging or a disguise for disconnection.

Even Uniqueness is Uniform

Of course, even this third option has its irony. If everyone stopped following trends and decided to express their unique selves through personal style, we’d likely still end up in a new kind of uniform.

Because if everyone is special, nobody is.

Individuality, once mass-adopted, becomes its own kind of conformity — just as curated as any seasonal lookbook.

So maybe the real work isn’t about what’s visible at all. Maybe it’s not about whether we conform or reject, blend in or stand out, but about the quieter question underneath all of it:

What are we hoping to find — or escape — when we choose to look like someone else, or even ourselves?