« Le corps est notre moyen général d’avoir un monde. »

“The body is our general medium for having a world.”

— Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Phenomenology of Perception

There are five body shapes you already know. They go by fruit metaphors or quiet geometry: apple, pear, strawberry, cherry, rectangle, triangle, hourglass, inverted triangle, oval.

You’ll find them in every style guide, every YouTube tutorial, every Pinterest explainer. What they all share is a focus on proportions: shoulders, waist, and hips — how they align, where they don’t, and most importantly: what you should do about it.

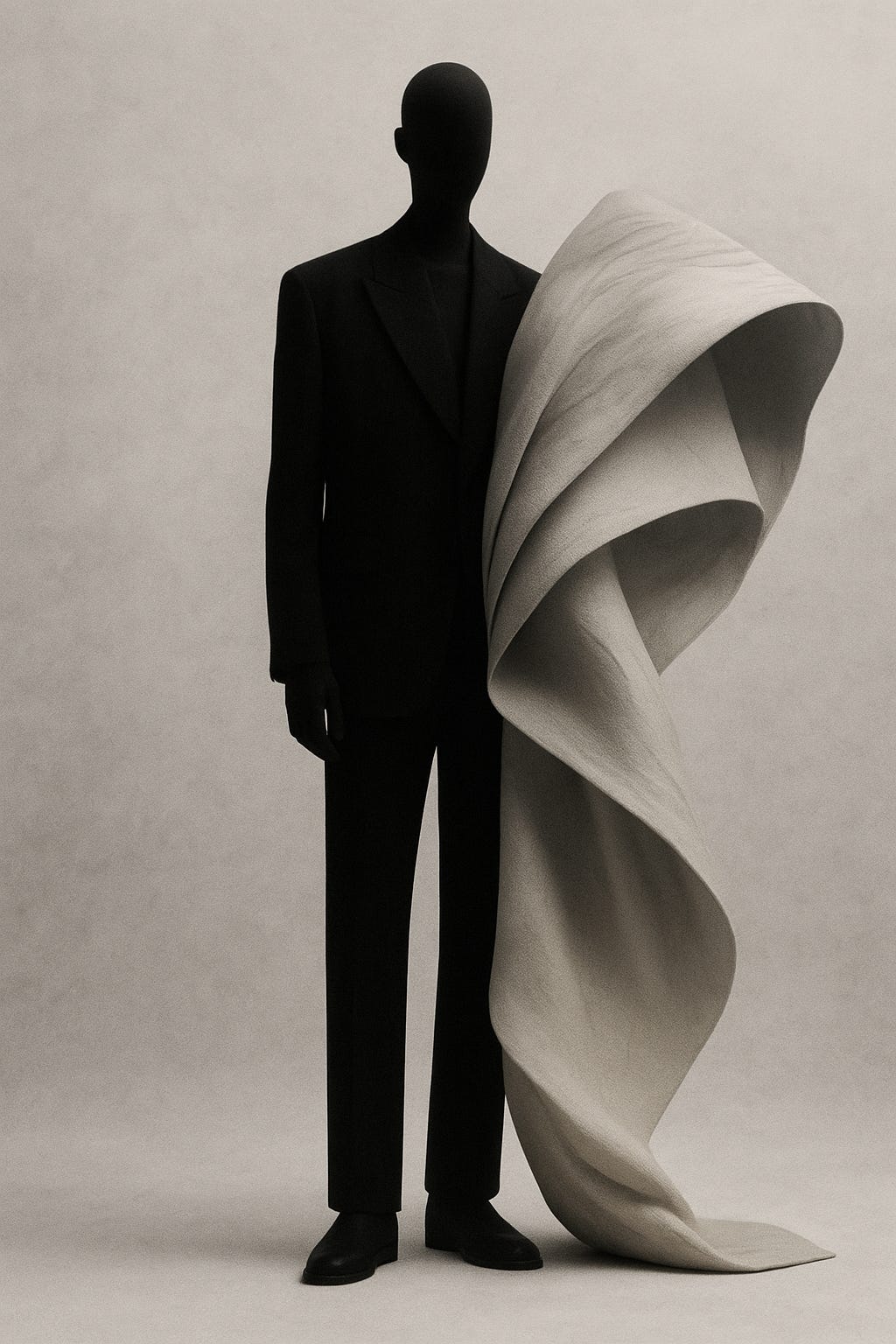

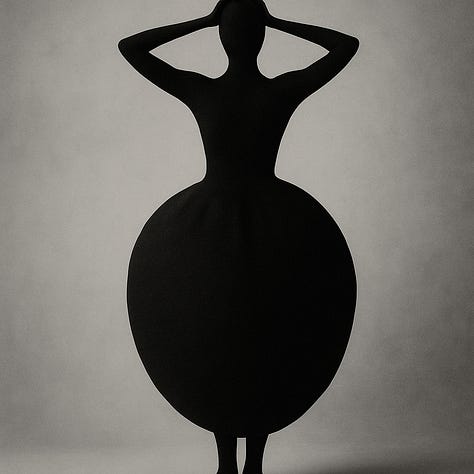

By nature, body shapes are a system rooted in correction and heavily based on ancient ideals — not individuals. I do believe in visual balance and the harmony of proportions, but instead of "fixing," I think we should ask how we can construct a shape. What shadow do you want to cast - what echo do you want to leave behind?

If the body, like in Merleau-Ponty’s theories, is viewed as the "starting point" — the medium to perceive and be perceived — then clothing, and thus the silhouette we create from it, becomes the extension of our embodied narrative. An authored perception.

A General Typology: Shapes, No Silent Judgment

Since we are talking about skeletal structures of the human body, instead of dividing people into male and female shape systems, we can define five base forms that apply to any body, regardless of gender identity (simply because it is that simple). These aren’t judgments. They are starting points. Anchors for construction, not conclusions:

Shape N — shoulders, waist & hips approx. same width

Shape V — shoulders broader than waist & hips

Shape A — hips wider than shoulders, narrow upper body

Shape X — shoulders & hips similar, with a visibly narrow waist

Shape O — waist wider than both shoulders & hips

Now add vertical scale:

Compact

Neutral

Elongated

While these base shapes are meant to be neutral in the sense of being free of judgment, it is important to note that naturally the human brain will subconsciously pick up on visual balance and proportion.

Height changes how proportions are perceived. A short Shape V and a tall one do not cast the same visual impact. The same goes for long torsos versus long legs. These modifiers — height, posture, limb length — are all part of how we read a body, whether consciously or not.

Posture, too, is rarely perceived neutrally. It carries history — both physical and psychological. It can speak of protection, performance, pride, or apology. And when you start to map your body in this more abstract way, what you begin to see is a kind of architecture: not a fixed form, but a flexible framework.

Silhouettes: From Conformity to Construction

Once you know your base form, you begin to shape your shadow — and here’s where it gets interesting.

Traditional styling teaches you to correct. Broaden the hips. Minimize the stomach. Elongate the legs. But what if you want to do the opposite? What if your goal isn’t balance, but emphasis? Not symmetry, but symbolism?

Your silhouette is not what you are — it’s what you choose to create.

Layering adds volume and texture, not just warmth.

Cinching redirects the gaze — it doesn’t merely define the waist.

Long lines elongate or abstract the figure.

Oversized fits shift gravity upwards or downwards.

You are no longer dressing to hide your “flaws.” You are dressing to design a presence.

A silhouette is a choice, but it’s also a hypothesis — a test. An invitation to experience yourself differently, even briefly. And that, in its quiet way, is a deeply philosophical act.

No more Apples & Pears

This theory doesn’t seek to replace the old system with new rules. It seeks to offer a vocabulary.

One that doesn’t require you to identify with a fruit or conform to a historical ideal.

One that says: here’s your base. Here’s your scale. Now — what do you want your shadow to say?

Because in the end, your style is not just about what you wear. It’s about what shape you choose to let the world see.

« Le corps n’est pas un objet, il est une situation : il est notre point de vue sur le monde. »

“The body is not an object, but a situation: it is our point of view on the world.”

— Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Phenomenology of Perception

And if the body is, as Merleau-Ponty writes, not a thing but a situation — then dressing is one of the most intimate ways we author that situation, silhouette by silhouette, shadow by shadow.

Final note

Ask yourself:

Do I want to command space, or slip through it?

Do I want to reveal — or redirect?

Do I want to soften my outline or sharpen it?

Do I want motion or stillness?

What part of me do I want to emphasize — and why?

These are not shallow questions. They are psychological. Symbolic. Sometimes even therapeutic.

This is shadow work of another kind. The shape we give ourselves — and the one we hide behind — is rarely accidental. It holds the imprint of fear, desire, defense, aspiration. Once you see your silhouette as a dialogue between these forces within you, you can begin to shape it with more care — or more chaos — depending on what you need that day.